March 2022 was when I first entered the realm of 10Gbps Internet with a Sonic fiberoptic plan, which has since proven to be an excellent service, at least in the San Francisco Bay Area. It was a game changer moving from Comast’s Xfinity cable Internet.

In the past few years, lots have changed. We now have Wi-Fi 7, and with it, routers equipped with 10Gbps ports are commonplace. Still, similar to the case of Gigabit broadband, getting true 10Gbps is not possible.

Among other things, this post will talk about the why and set some expectations. Most importantly, after years of daily experience, I’d say that we simply don’t need 10Gbps Internet, and in all cases, this speed grade is a luxury.

So, the real question is, would that be worth the investment? We’ll find out, considering achieving (close to) 10Gbps bandwidth can still be quite expensive today, and by that, I don’t mean the broadband subscription itself.

Dong’s note: I first published this piece on March 30, 2022, and last updated it on February 11, 2025, to add up-to-date, relevant information.

10Gbps Internet: Moving the bottleneck from broadband to local hardware

For years, the sub-Gigabit broadband connection has always been the bottleneck in our connection to the outside world—it still is today for many. That’s because if your Internet speed is 100Mbps, you can’t download anything faster than 100Mbps on a good day, no matter how fast your local network is.

Even Gigabit-class Internet—something between 500Mbps to 1Gbps—is still slower than Wi-Fi. Starting with Wi-Fi 6, Gig+ is a typical sustained rate.

Data transmission speeds in a nutshell

As you read this page, note that each character on the screen, including a space between two words, generally requires one byte of data.

Byte—often in thousands or kilobytes (KB), millions or megabytes (MB), billions or gigabytes (GB), trillions or terabytes (TB)—is generally used to convey storage space to total data usage. For data transmission, we use bits.

One byte equals eight bits.

One million (1,000,000) bits = 1 Megabit (Mb).

Megabits per second (Mbps)—the number of megabits being manipulated in one second—is the standard unit for data transmission nowadays. Based on that, the following are common terms:

- Fast Ethernet: A connection standard that can deliver up to 100Mbps.

- Gigabit: That’s short for Gigabit Ethernet (GbE) and generally means transmission speeds in Gigabit per second (Gbps), currently the most popular wired connection standard. 1Gbps = 1000Mbps.

- Gig+: A connection that’s faster than 1Gbps but slower than 2Gbps. It often applies to 2×2 Wi-Fi 6/6E or broadband Internet speeds.

- Multi-Gigabit: A link that’s 2Gbps or faster. This often applies to Multi-Gig or Wi-Fi 7 hardware.

- Multi-Gig: A new BASE-T wired connection standard that delivers 2.5GbE, 5Gbe, or 10GbE over CAT5e (or a higher grade) network cables, depending on the devices involved, and is also backward compatible with Fast Ethernet and Gigabit.

As a result, with Gigabit or slower broadband, it’s incorrect to use an Internet speed test application to gauge your Wi-Fi performance—the best number you get is that of the former, the bottleneck. I ranted long and hard about that in this post on speed testing.

A 10Gbps—that’s 10Gigabit Ethernet, a.k.a 10GE, 10GbE, or 10GigE—broadband connection changes all that. The Internet is now the fastest pipe in your home. But it also brings about another headache for those wanting to get the absolute most out of this world-bound highway.

Setting the right expectation

Here’s a fact: current networking devices feature 10Gbps as the highest port grade. Consequently, they can’t deliver 10Gbps in full—hardware has overhead. In other words, there’s no way for us to experience true 10 Gigabit Internet with existing equipment.

I can say that with a high level of confidence because in the past three years, I’ve tested dozens of 10Gbps routers, mesh systems, and switches, and none could deliver 9000Mbps in real-world sustained performance, as shown in the chart below.

In other words, if you want to see a real 10Gbps sustained rate, you will need equipment that can handle 20Gbps or faster. We’ll get there at some point, but for now, that’s not in the foreseeable future simply because it’s not necessary. In fact, 10Gbps is already unnecessary in all cases.

So, we’re now talking about being happy with “sorta 10Gbps” connectivity, or “10Gbps-class”. Still, things remain challenging. I speak from years of experience.

Let’s start with the hardware.

10Gbps on the client end: Wired only, and it’s tricky

Below is a screenshot of the current Internet speed on my work computer. It’s fast, alright, but you’ll note that it’s not 10Gbps, only around 2.5Gbps. Did I get ripped off? Nope.

My desktop computer used for the test has a built-in 2.5Gbps Multi-Gig network adapter. And the Internet connection saturated that multi-Gigabit connection. You’ll note that the number is slightly lower than 25000Mbps—again, hardware, the port in this case, has overhead.

There are very few motherboards with built-in 10Gbps network ports—they often have the 2.5Gbps and 5Gbps port grades instead. That said, on a computer, you generally need to upgrade to 10Gbps via Thunderbolt or PCIe adapters, which are not cheap.

Upgrading a desktop computer to 10Gbps Multi-Gig is similar to upgrading it to Wi-Fi 6/E. You get an add-on card, assemble it on a qualified PCIe slot, and install the software.

The biggest and only difference is a 10Gbps NIC card requires a four-lane (x4) or faster PCIe slot instead of a single-lane (x1).

On most desktop motherboards, the only qualified PCIe slot is the 16-lane, generally reserved for a dedicated graphics card. In this case, you can only upgrade if you use the computer’s basic integrated (onboard) graphic processing unit (GPU).

How about Wi-Fi, you might ask? In my experience, even the best-to-date Wi-Fi connection—a 2×2 Wi-Fi 7 card using a 320MHz channel width—sustains at around 3500 Mbps of real-world rates in a best-case scenario. It’s virtually impossible to experience 10Gbps via Wi-Fi.

So, if you want to experience 10Gbps, upgrading your computer to a 10Gbps wired adapter is the only way for now. But even then, that’s only half of the equation. You need a router and possibly a switch of the same caliber, too.

10Gbps Internet on the router end: Generally expensive

In the past few years, routers with Multi-Gig ports have become the norm. However, those with two or more 10Gbps ports are still somewhat of a luxury simply because they are expensive.

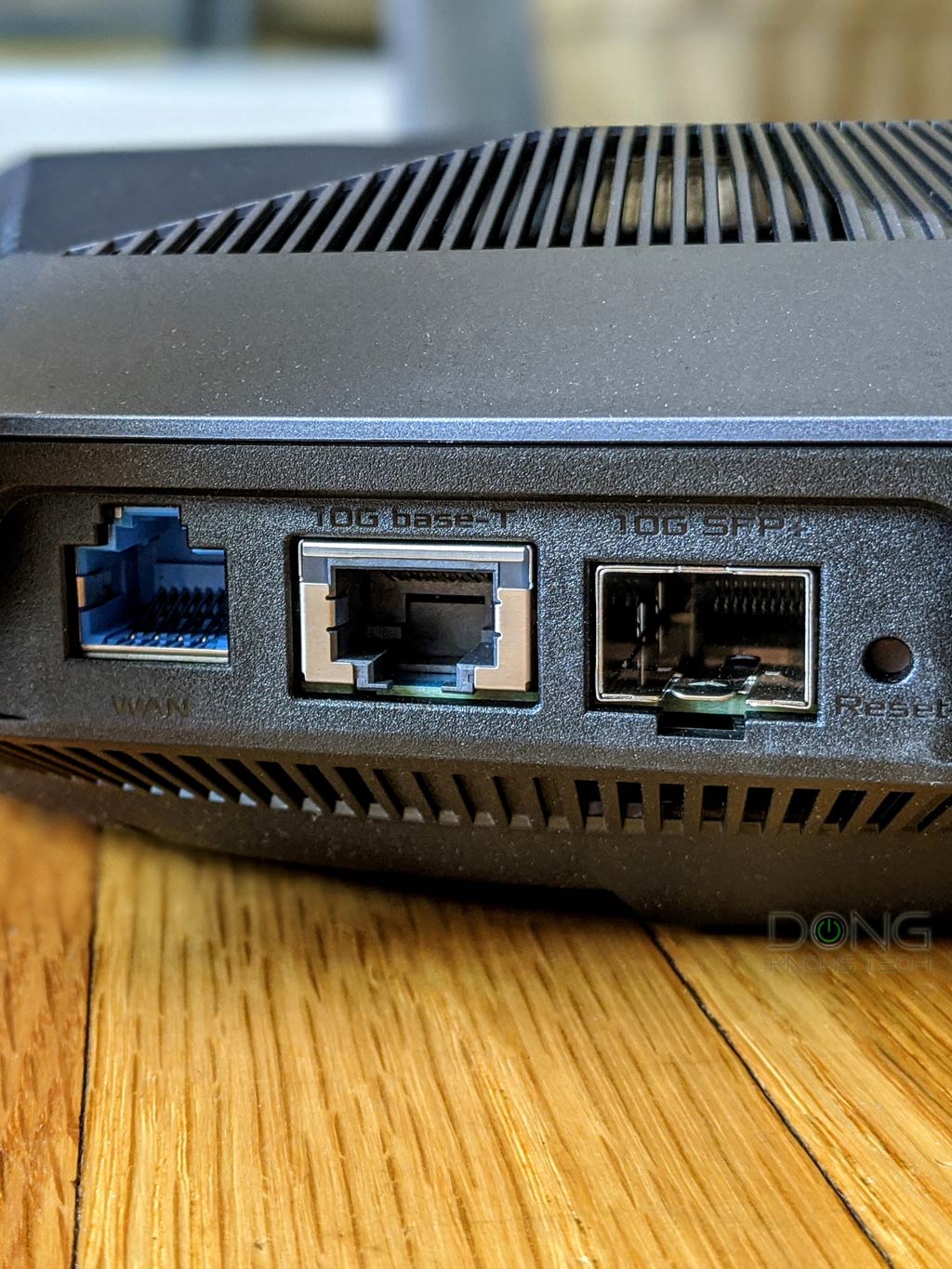

You need, at minimum, two ports on a router to form a 10Gbps connection, one on the WAN side and the other on the LAN side. The 10Gbps LAN port also allows you to expand the network with the same grade via a switch.

Notes on 10Gbps hardware

A router needs more than just a couple of 10Gbps Ethernet network ports to deliver (close to) true 10Gbps. It also requires high processing power and applicable firmware to handle this bandwidth.

Generally, consumer-grade Multi-Gig routers and switches do not deliver true 10Gbps (10,000Mbps) throughputs. After “overhead”, they sustain approximately between 6.5Gbps (Wi-Fi 6/6E hardware) and 8.5Gbps (Wi-Fi 7 hardware). Often, a router’s traffic-related features, such as QoS, security, etc., when turned on, can impact its bandwidth.

Many home Wi-Fi routers support the entry-level Multi-Gig, which is 2.5Gbps and can deliver close to 2,500Mbps in real-world speeds.

Below is the frequently updated list of the best routers with 10Gbps ports. Again, as noted in the performance chart above, none of them could deliver true 10Gbps real-world speed, and they are all quite expensive.

I tested all of these devices with my 10Gbps broadband, and the best result I’ve gotten in the past few years was around 8500Mbps.

By the way, not all routers (or switches) came with the all BASE-T 10Gbps port. Some have one or two of the less common SFP+, which can be turned into a BASE-T via an adapter. In some cases, the SFP+ port on a router can come in handy if the fiberoptic ONT uses the same port type.

Extra: BASE-T vs. SFP+

BASE-T (or BaseT) is the standard port type for data communication and refers to the wiring method used inside a network cable and the connectors at its ends, which is 8-position 8-contact (8P8C).

On the other hand, the SFP or SFP+ (plus) port type is used for telecommunication and data communication, primarily in enterprise applications. SFP stands for small form-factor pluggable and is the technical name for what is often referred to as Fiber Channel or Fiber.

For data communication, an SFP+ port has speed grades of either 1Gbps or 10Gbps. The older version, SFP, can only do 1Gbps, though it shares the same port type as SFP+. This type of port standard is more strict in compatibility with better reliability and performance.

While physically different, BASE-T and SFP/+ are parts of the Ethernet family, sharing the same networking principles and Ethernet naming convention—Gigabit Ethernet (1Gbps), Multi-Gig Ethernet (2.5GBASE-T, 5GABSE-T), or 10 Gigabit Ethernet (a.k.a 10GE, 10GbE, or 10 GigE).

The BASE-T wiring is more popular thanks to its simple design and speed support flexibility. Some routers and switches have an RJ45/SFP+ combo, which includes two physical ports of each type, but you can use one at a time.

With a router, you’ll be able to have a single 10Gbps connection. To connect more wired clients at 10Gbps, as mentioned, you’ll need a switch. Or you have to opt for a mesh system.

10Gbps-capable switches or mesh system: Another expensive investment

While Gigabit switches are a dime a dozen and relatively affordable, Multi-Gig switches, especially those capable of 10Gbps, have not come down in price.

For example, the Zyxel XS1930-12HP, which was fireset leased more than four years ago, still costs around $700 today. Those with fewer ports go for less, but still, you’ll need to spend a few hundred dollars on one.

Alternatively, if you have a large home, you might want to get a 10Gbps-capable mesh system instead of a router and a switch. In this case, be prepared for another sticker shock. Below is the frequently updated list of the best five 10Gbps Wi-Fi systems you can bring home today, and you guessed it! None is affordable.

So, in the end, to experience 10Gbps-class Internet, you’ll need to spend over $1000 on equipment alone.

In my case, I’ve used all of the hardware mentioned here, and that brings us to my actual Internet speed out of my 10Gbps fiberoptic broadband.

My actual Multi-Gig Internet speed

Years ago, upon completing the installation, the Sonic technician did a test at the ONT with his special equipment, which showed around 8Gbps on download and upload speeds. Over the years, the number fluctuated, but the fastest I’ve gotten is in the screenshot below: around 8.5Gbps in both directions.

It’s worth noting that I got the results above when tested directly at the ONT. When tested via my main router with a switch in between, I generally get around 6Gbps at best. Again, more equipment means more overhead.

Here’s the thing, though: I simply stop caring. The truth of the matter is that 2.5Gbps, which is what I get most of the time using my work desktop, is already crazy fast. Anything above that is simply not noticeable.

Fiberoptic broadband is so much better than cable, by the way. The speed aside, I consistently get ping and jitter values, which determine the quality of a connection, below a few milliseconds. In many tests, they were at zero.

Multi-Gig Internet and its hidden benefits

True 10Gbps or not, my broadband connection is now easily in the Multi-Gig realm. The ultra-fast speeds, apart from being fast, also bring in some advantages you can’t have with sub-Gigabit.

QoS is (mostly) no longer applicable

The first is that you don’t need to use Quality of Service anymore. I wrote about QoS in this post, but it’s a function that prioritizes the broadband connection to prevent a device from hogging all the bandwidth.

Considering most devices have Gigabit or Wi-Fi at best, the network adapter is now the bandwidth guardrail. For example, if you host a BitTorrent client on a computer with a Gigabit connection, the client can use no more than 1000Mbps of Internet bandwidth at any given time. Supposedly, you still have some 9000Mbps for other things—it’s a matter of bandwidth.

If you use multiple clients like that, then it might still be a good idea to use QoS. But you get the idea.

Bandwidth vs. speed

When it comes to a data connection, we tend to think of speed, as how fast data moves from one party to another, generally measured in bits per second.

For a slow connection, we use kilobit (Kbps), for faster ones, we use megabit (Mbps) or Gigabit (Gbps).

When you get a broadband plan, the number of bits also indicates its bandwidth. A Gigabit plan (1000Mbps) allows two devices to connect at 500Mbps simultaneously. With a 10Gbps plan, you can do that on 20 concurrent 500Mbps-capable devices.

That’s why fast broadband is still applicable when there are only slow devices within a network.

By the way, in my case, the fiberoptic line significantly improves real-time communication thanks to the better connection quality.

A new level of personal server

Thanks to the much faster upload speed, all personal remote server applications work much better.

My business partners and I use several Synology NAS servers in multiple locations and sync data between them as off-site backups. The super-fast broadband—and the omission of a monthly data cap—makes this much better, at least at my end.

If you use a personal media server, such as Plex, streaming content from your NAS server when you’re on the go is now just like using Netflix or Hulu in terms of speed and video quality. Actually, it was better in my trial.

With 10 Gigabit Internet, the broadband speed test is now applicable for local Wi-Fi testing

This part applies directly to what I do on this website. In the past few years, I often used the Internet speed test as a supplemental testing method since it was determined to be faster than the fastest Wi-Fi connection.

I still use my current test methodology, but knowing that the Internet is no longer the bottleneck has made my work much easier. For example, I have been able to determine whether a router is consistent on both the LAN and WAN sides, whether its WAN port is truly Multi-Gig and more.

The takeaway

Again, it’s impossible to get a real sustained 10Gbps connection—we need faster-than-10Gbps equipment for that.

That said, unless cost is not an issue, getting a 5Gbps or slower broadband will give you the best bang for your buck since you’ll be able to experience it in full (with 10Gbps equipment). Also, keep in mind that 2.5Gbps is more than fast enough in most if not all, cases.

The point is that 10Gbps broadband or local bandwidth is fun and doesn’t hurt to have if you don’t have to pay an arm and a leg for it. But at the end of the day, you only need the connection fast enough for your application at a given time. Anything above that becomes practically meaningless, and if you’re obsessed with speed-testing, that’ll cost you both time and cash for top-tier equipment.